(NEW YORK) — President Donald Trump’s redistricting push to preserve a Republican majority in Congress and allied voting rights cases in Texas and Louisiana could wipe out nearly a third of the 62-member Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) if all the electoral and judicial dominoes fall his way.

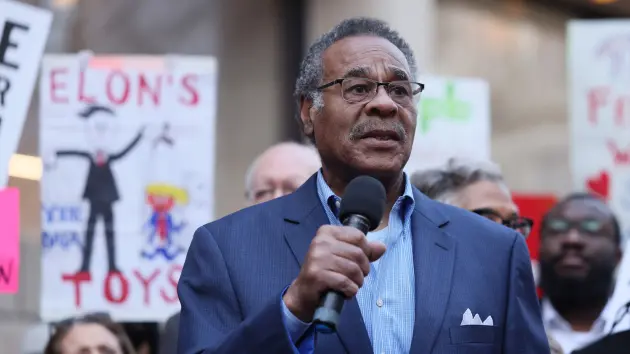

Missouri Democratic Rep. Emanuel Cleaver, who has served 11 terms in the House, called the efforts as “blind, and sometimes even mean-spirited, political decisions that those who perpetuate it could easily deny it.”

Cleaver’s district is one of those in the crosshairs of Trump’s march to enlist statehouses and the courts to increase Republican seats in Congress at the expense of Democrats — many longstanding, dozens of them Black and Brown.

“There are probably some good and decent people who, but for their cult-like political attitudes, would not like something like this to happen,” Cleaver added as he tried to make sense of how he and his district are threatened by what he says is a double-barreled salvo aimed at the Voting Rights Act and state legislatures.

Cleaver’s senior colleague from South Carolina was more blunt.

“These are people who are trying to rig the system, making it very clear that there are certain people who will not be represented in Congress,” said Democratic Rep. James E. Clyburn, who has worn multiple House leadership titles along with being a Presidential Medal of Freedom holder. He has represented the Palmetto State since 1993 and, like Cleaver, once led the CBC — a staple of Capitol Hill politics since 1971.

On Monday, a coalition of voters of color and civil rights advocates will ask the Supreme Court to maintain a lower court’s ruling that Texas Gov. Greg Abbott’s redrawn map is an illegal racial gerrymander.

Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito temporarily paused the lower court’s order last week.

The Texas maps were set in motion by Abbott at the behest of Trump, who has openly called on Republican-controlled statehouses and governors to pass maps so that his party gains more seats and maintains control of Congress.

“A very simple redrawing; we pick up five seats. And we have a couple of other states where we’ll pick up seats also,” Trump said of Texas and other efforts in July.

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act

The effect of the new maps in Texas, Louisiana and elsewhere puts at risk so-called “majority-minority” seats made possible by Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which prevents any voting procedure or practice which results in a denial of the right to vote using race, color, or even language minority status.

It is also the main legal tool used to challenge election laws, like district maps, which may have a discriminatory result, even if that wasn’t the intent.

Such a challenge under Section 2 may lead to the creation of a majority-minority district where a racial minority group makes up the majority of the voting-age population. The goal in the case of such a district is to give the minority, racial or language group a realistic chance to elect the representative of their choice.

Many of those majority-minority districts are held by African American and Latina/Latino members. Some political and legal analysts say up to 19 members of the CBC stand to be wiped out.

Cleaver, whose Kansas City-area district would be cut in two in a redrawn Missouri map, told ABC News that the effort is part of an overall step backward when it comes to racial representation.

“We are just tearing apart a district in order to satisfy someone’s desire for reelection,” Cleaver told ABC News in September.

Clyburn said “It’s pretty clear what it’s about: What they’re trying to do now is render Section 2 ineffective.”

He added, “You got to hope that the Supreme Court will not take it up … The Supreme Court can stay out of it, and then what the law court has already done, it will stand. And there are a lot of people who think that may be the case.

“I hope the Supreme Court collectively will come to understand that they have unleashed severe threats to those constitutional principles that have kept this country together for all of these years.”

Louisiana’s congressional map was redrawn in 2022 because it violated the Voting Rights Act Section 2 by discriminating against African American voters.

The Pelican State went back to the drawing board to create a new map to follow the law. The majority-minority districts are now in front of the Supreme Court as to whether they violate the Constitution.

Janai Nelson, president and director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, called that challenge “specious and wrong.”

Republicans contend their redrawn maps are not about race but are driven by a desire for partisan advantage — something the Supreme Court has ruled is constitutional.

Abbott defended Texas’ redistricting effort, saying race had nothing to do with it and calling a lower court decision “clearly erroneous.”

“The Legislature redrew our congressional maps to better reflect Texans’ conservative voting preferences — and for no other reason,” Abbott said in a statement. “Any claim that these maps are discriminatory is absurd and unsupported by the testimony offered during ten days of hearings. This ruling is clearly erroneous and undermines the authority the U.S. Constitution assigns to the Texas Legislature by imposing a different map by judicial edict.”

Nelson said “Despite the Supreme Court’s permissiveness around partisan gerrymandering, this certainly is unconstitutional and is a case that they take up. I think the three-judge panel was quite clear on what the violations were. It was clear from the very beginning that the intention is to dilute the voting power of Black and Latino communities in Texas.”

Protecting vulnerable members

Cleaver acknowledged the reality of fighting it out in state legislatures.

“We’re minorities politically. So, it’s not like we can submit a piece of legislation to make it right,” Cleaver told ABC News. “We’re going to lose on all of the votes.”

He said Rep. Gregory Meeks, chair of the CBC’s political action committee CBC-PAC, has identified vulnerable members who the group aims to put on a “protection plan.” Some of those members include Louisiana Reps. Troy Carter and Cleo Fields, Alabama Reps. Terri Sewell and Shomari Figures, Georgia Rep. Lucy McBath, Texas Reps. Al Green, Marc Veasey and Jasmine Crockett, Mississippi’s Bennie Thompson, Florida Rep. Sheila Cherfilus-McCormick and Clyburn.

The CBC-PAC will raise money for candidates who are “fighting for survival in these places where they were redistricted and left to win in a district that’s not normally responsive to us,” Cleaver said.

Members of other ethnic groups who are vulnerable include Texas Reps. Vicente Gonzalez, Joaquin Castro and Julie Johnson.

Cleaver said campaigning in the proposed new districts amounts to surrender.

“If you start saying, ‘I want to go out and start campaigning in the proposed district,’ you are actually playing right into the hands of the people who are trying to eliminate you. If we think we’re right, we ought to act like we are right,” he said.

Clyburn, a big ground-game supporter, backs efforts to pass referendums such as one building signature support in Missouri to block the new congressional map recently passed and signed by Gov. Mike Kehoe. The new map takes effect in early December, or 90 days after the end of the state’s legislative session, unless opponents collect enough signatures to put the new map to a vote.

However, the effort by referendum advocacy group People over Politicians, which claims it has the necessary signatures to put the new map to a vote is being challenged in court by secretary of state and the state General Assembly, which contends on constitutional grounds that the legislature’s authority over redistricting cannot be overturned by referendum.

People over Politicians says the Republican-led government’s argument is an attempt to justify a “power grab. A federal judge he’ll the matter by Dec. 9, two days before the deadline for gathering signatures for a referendum.

Until then, Cleaver is comforted by those fighting on his behalf which includes an unusual and large coalition of multi-racial clergy, grassroots activists and business leaders who normally are silent. “So, you know we’re not, those of us who are in office. We’re not alone. We’re not alone.”

Effect of striking down majority-minority districts

So, what, at the end of the day, do the Louisiana and Texas Voting Rights Act-related cases mean for the law itself if majority-minority districts are struck down by the Supreme Court? Nelson explains both the practical and constitutional stakes.

Nelson said there are up to 19 districts that have been protected by or drawn in response to the Voting Rights Act. She explained the practical and constitutional stakes if majority-minority districts are struck down by the Supreme Court:

“And we expect that, you know, states that are opposed to, you know, shared power among people of all races and backgrounds will leap at the opportunity to redraw maps in a way that shuts out a significant portion of our electorate from ever being able to elect candidates of their choice.”

Nelson said such a move by the court “would be a colossal undercutting of power that would then translate into even more failed policies for some of the most vulnerable communities in our country. So the impact would be absolutely devastating,” she said. “This is not just, you know, political warfare or partisan competition. This is making a mockery of a representative democracy when you don’t have fair representation.”

Clyburn for his part would rather mobilize than wait for parties out of his control to act.

“We need to be involved, to turn out the vote and do what we can to make sure that people get to the polls, and hopefully do what is necessary to stop the redistricting at the polling places. That’s what we can do,” he said. “To sit around wringing our hands about what the court may or may not do is a waste of time, energy, and, I think, emotions.”

Copyright © 2025, ABC Audio. All rights reserved.